Learning Together

Insights from the Professional Learning with Impact Program

Designing teacher professional learning programs

Teachers are at the heart of our education system. Their role is even more critical for students from families with low-income or other disadvantages.

One way school systems can support strong teaching is through programs that build teachers’ knowledge and skills—teacher professional learning programs. But designing professional learning programs to be scalable and effective is difficult.

In 2018, the American Institutes for Research® (AIR®) launched a project to address this challenge. AIR engaged The Danielson Group and Learning Forward to design and scale the Professional Learning with Impact (PLI) program.

AIR then conducted a randomized controlled trial to see if the PLI program was effective in high-need schools. The U.S. Department of Education supported the project with an Education Innovation and Research grant.

Scroll down to discover:

- What is the Professional Learning with Impact (PLI) program?

- What did the randomized controlled trial find?

- What insights did the project produce about grade-level team meetings?

- What was learned about scaling professional learning programs?

What is the PLI program?

The design of the PLI program draws on the evidence base on teacher professional learning.

To design the PLI program, the partners built on evidence about teacher professional learning strategies that lead to improved student outcomes. In three studies, providing teachers regular feedback using a validated classroom observation instrument—specifically —Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (FFT) had a positive impact on student achievement.

What is the Framework for Teaching?

The FFT is a comprehensive tool for teacher self-assessment and reflection, observation and feedback, and collaborative inquiry that specifies several dimensions of an educator's professional practice. For each dimension, it describes four distinct levels of performance. These descriptions help educators think and talk about the quality of instruction. The FFT Clusters is a more recent version of the FFT, designed to be easier to use.

The PLI program incorporates the FFT into three professional learning activities.

Because the FFT is widely used for observation and feedback including teacher evaluation, the partners sought other ways teachers could use the FFT. The PLI program’s three professional learning activities each use the FFT. The activities are:

- Workshops

- Teacher Learning Teams (TLTs); and

- Individual Coaching

Complete details about each component appear in the PLI Guidebook.

For the project and its randomized controlled trial, the participating schools implemented the PLI program for two years in a single grade level—either grade 4 or 5. In each district, the partners provided the workshops to the grade-level teams from the participating schools. And within each school, a local coach led the teacher learning team meetings and individual coaching.

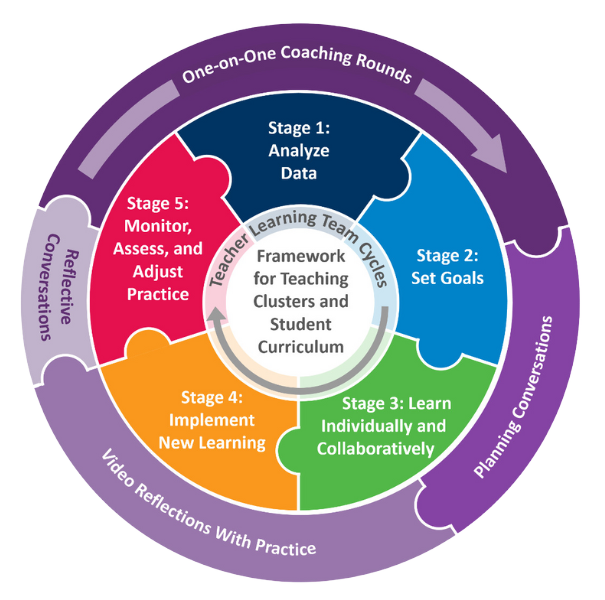

Three Interconnected Professional Learning Activities

The PLI coaches were expected to lead the TLTs through a 5-stage inquiry cycle which could provide continuity across the meetings. Many models for professional learning communities use similar inquiry cycles. The meetings, supported by structured protocols, are designed to foster collaborative learning and goal achievement.

What is the PLI program?

The design of the PLI program draws on the evidence base on teacher professional learning.

To design the PLI program, the partners built on evidence about teacher professional learning strategies that lead to improved student outcomes. In three studies, providing teachers regular feedback using a validated classroom observation instrument—specifically —The Danielson Group’s Framework for Teaching (FFT) had a positive impact on student achievement.

What is The Danielson Group’s Framework for Teaching?

The FFT is a comprehensive tool for teacher self-assessment and reflection, observation and feedback, and collaborative inquiry that specifies several dimensions of an educator's professional practice. For each dimension, it describes four distinct levels of performance. These descriptions help educators think and talk about the quality of instruction. The FFT Clusters is a more recent version of the FFT, designed to be easier to use.

The PLI program incorporates the FFT into three professional learning activities.

Because the FFT is widely used for observation and feedback including teacher evaluation, the partners sought other ways teachers could use the FFT. The PLI program’s three professional learning activities each use the FFT. The activities are:

- Workshops

- Teacher Learning Teams (TLTs); and

- Individual Coaching

Complete details about each component appear in the PLI Guidebook.

For the project and its randomized controlled trial, the participating schools implemented the PLI program for two years in a single grade level—either grade 4 or 5. In each district, the partners provided the workshops to the grade-level teams from the participating schools. And within each school, a local coach led the teacher learning team meetings and individual coaching.

Three Interconnected Professional Learning Activities

The PLI coaches were expected to lead the TLTs through a 5-stage inquiry cycle which could provide continuity across the meetings. Many models for professional learning communities use similar inquiry cycles. The meetings, supported by structured protocols, are designed to foster collaborative learning and goal achievement.

What did the study find?

The PLI program had a positive impact on students’ ELA achievement.

AIR randomly assigned schools to implement the PLI program or serve in a control group. Using this randomized controlled trial design, researchers can measure a program’s impact by comparing outcomes across schools at the end of the program.

After two years, the study found that the PLI program had a positive impact on students’ achievement in ELA. The impact on ELA achievement was particularly strong for students who were considered English learners. However, the study found no statistically significant impacts on students’ achievement in math or the study’s measures of teacher self-efficacy or the quality of classroom practice.

What caused the impact?

Data points to workshops and TLT meetings, rather than individual coaching.

According to the study’s implementation data, a little under two-thirds of teachers engaged in any individual coaching, and the average coaching “dose” was minimal. Thus, what caused the positive impact on achievement was most likely the other two components: the workshops and the TLT meetings.

Implementation Summary

The teachers participated in the workshops and teacher learning teams (TLT) but not the individual coaching.

Workshops. The workshops were implemented as intended, involving 3 events spread across the first school year. In a total of 15 hours, these events prepared teachers to implement the TLTs and supported them while the TLTs were underway.

Teacher Learning Teams (TLTs). The TLTs met an average of 18 times across the 2 years. The PLI partners trained local coaches to facilitate the TLT meetings and lead teachers through “inquiry cycles.” The implementation data show that the teams did not always follow the meeting protocol, but teams on average completed about three inquiry cycles.

Individual Coaching. The individual coaching occurred only rarely. Across the two years, the local coaches (i.e., PLI coaches) were expected to do four “rounds” of coaching with each teacher. The average number of coaching rounds completed was near zero.

Why was there an impact on ELA but not math?

The study’s implementation data suggest that there may be a simple answer to this question. The grade level teams generally set goals related to student outcomes broadly or to ELA achievement. Only one school’s TLT chose a goal related to math achievement.

These implementation findings may also explain why the impact on ELA achievement was particularly strong for students who were considered English learners.

What did the study find?

The PLI program had a positive impact on students’ ELA achievement.

AIR randomly assigned schools to implement the PLI program or serve in a control group. Using this randomized controlled trial design, researchers can measure a program’s impact by comparing outcomes across schools at the end of the program.

After two years, the study found that the PLI program had a positive impact on students’ achievement in ELA. The impact on ELA achievement was particularly strong for students who were considered English learners. However, the study found no statistically significant impacts on students’ achievement in math or the study’s measures of teacher self-efficacy or the quality of classroom practice.

What caused the impact?

Data points to workshops and TLT meetings, rather than individual coaching.

According to the study’s implementation data, a little under two-thirds of teachers engaged in any individual coaching, and the average coaching “dose” was minimal. Thus, what caused the positive impact on achievement was most likely the other two components: the workshops and the TLT meetings.

Implementation Summary

The teachers participated in the workshops and teacher learning teams (TLT) but not the individual coaching.

Workshops. The workshops were implemented as intended, involving 3 events spread across the first school year. In a total of 15 hours, these events prepared teachers to implement the TLTs and supported them while the TLTs were underway.

Teacher Learning Teams (TLTs). The TLTs met an average of 18 times across the 2 years. The PLI partners trained local coaches to facilitate the TLT meetings and lead teachers through “inquiry cycles.” The implementation data show that the teams did not always follow the meeting protocol, but teams on average completed about three inquiry cycles.

Individual Coaching. The individual coaching occurred only rarely. Across the two years, the local coaches (i.e., PLI coaches) were expected to do four “rounds” of coaching with each teacher. The average number of coaching rounds completed was near zero.

Why was there an impact on ELA but not math?

The study’s implementation data suggest that there may be a simple answer to this question. The grade level teams generally set goals related to student outcomes broadly or to ELA achievement. Only one school’s TLT chose a goal related to math achievement.

These implementation findings may also explain why the impact on ELA achievement was particularly strong for students who were considered English learners.

What insights did the project produce about grade-level team meetings?

The findings about impact and implementation point to the grade-level team meetings (i.e., the TLT meetings) as the most likely driver of the positive impact on ELA achievement. In testimonial evidence gathered by AIR several months after the program ended, participants shared their perspectives on what was helpful about the TLT meetings.

The PLI coaches who facilitated the TLT meetings valued the ongoing support from PLI partner staff.

The partners anticipated that PLI coaches would need ongoing support to facilitate the TLT meetings effectively. The PLI coaches joined monthly coach meetings led by the partners’ staff, called PLI Program Specialists. The coaches also met with the specialists individually each month. Several coaches found the support crucial.

The PLI coaches who facilitated the TLT meetings valued the ongoing support from PLI partner staff.

The partners anticipated that PLI coaches would need ongoing support to facilitate the TLT meetings effectively. The PLI coaches joined monthly coach meetings led by the partners’ staff, called PLI Program Specialists. The coaches also met with the specialists individually each month. Several coaches found the support crucial.

The leadership of a well-trained and supported coach helped teachers feel comfortable engaging in the grade-level teams.

The districts that joined the project said that their normal practice was to arrange teachers’ weekly schedules to allow them to meet in grade-level teams. They left it to teachers to decide how to use that time.

To convene and facilitate the PLI program’s TLT meetings, the program empowered local instructional coaches (i.e., the PLI coaches). Teachers commented on how the facilitation brought not only structure but also comfortable working relationships. Those working relationships enabled them to use the time well.

The PLI inquiry cycle and the goals set by grade-level teams provided structure and focus to team dialogue and collaboration.

The first two stages of the PLI collaborative inquiry cycle are “Analyze Data” and “Set Goals.” The goal each team set became a focus for sharing and collaboration about how to accomplish it. Teachers reflected in a way that was purposeful and centered on the goal.

In addition, having an inquiry cycle created continuity across meetings. The cycle specified five stages. Thus, the PLI coaches could keep the grade-level teams oriented across meetings, and decisions from one meeting provided direction and context for later meetings.

The leadership of a well-trained and supported coach helped teachers feel comfortable engaging in the grade-level teams.

The districts that joined the project said that their normal practice was to arrange teachers’ weekly schedules to allow them to meet in grade-level teams. They left it to teachers to decide how to use that time.

To convene and facilitate the PLI program’s TLT meetings, the program empowered local instructional coaches (i.e., the PLI coaches). Teachers commented on how the facilitation brought not only structure but also comfortable working relationships. Those working relationships enabled them to use the time well.

The PLI inquiry cycle and the goals set by grade-level teams provided structure and focus to team dialogue and collaboration.

The first two stages of the PLI collaborative inquiry cycle are “Analyze Data” and “Set Goals.” The goal each team set became a focus for sharing and collaboration about how to accomplish it. Teachers reflected in a way that was purposeful and centered on the goal.

In addition, having an inquiry cycle created continuity across meetings. The cycle specified five stages. Thus, the PLI coaches could keep the grade-level teams oriented across meetings, and decisions from one meeting provided direction and context for later meetings.

What was learned about scaling professional learning programs?

AIR and the partners wanted the PLI program to be not only effective but also readily-scaled. What was learned about scaling PLI and professional learning programs like it?

Some insights came from the project’s scaling phase. In the 2023-24 school year, we talked with several districts about PLI, so we could learn what aspects of PLI are most appealing, and then we gave them the opportunity to try it. The project’s digital story on scaling highlights these and other lessons.

Program designs need to incorporate a role for school leaders that includes advance planning and ongoing support.

During the two-year impact study (2021-2023), informal feedback led the partners to conclude that implementation would be easier and more successful if the PLI program included a role for school leaders. School leaders help grade-level teams preserve time to meet, and school leaders often determine priorities for local coaches.

This insight led the partners to develop a PLI component for leadership. When the scaling phase began, the partners included it in the PLI program.

Districts and schools are more likely to adopt a program when they can choose which program practices to implement and start small.

During the scaling phase, several districts considered participating but had concerns. The PLI program looked promising but implementing the program as a whole, all at once, in multiple schools would be challenging. They wanted to choose specific components and start small.

When offered that flexibility, the districts signed up. They selected components that mattered to them and wouldn’t interfere with other practices. For example, one district identified a need to build instructional coaching skills and start to establish a consistent approach to coaching. Two districts selected a single school to try the selected program components, with one focusing only on two grade-levels.

The flexibility allowed the district and school leaders to see what aspects of the PLI program fit their needs and consider what they might carry into the year ahead at additional grade levels and schools.

What was learned about scaling professional learning programs?

AIR and the partners wanted the PLI program to be not only effective but also readily-scaled. What was learned about scaling PLI and professional learning programs like it?

Some insights came from the project’s scaling phase. In the 2023-24 school year, we talked with several districts about PLI, so we could learn what aspects of PLI are most appealing, and then we gave them the opportunity to try it. The project’s digital story on scaling highlights these and other lessons.

Program designs need to incorporate a role for school leaders that includes advance planning and ongoing support.

During the two-year impact study (2021-2023), informal feedback led the partners to conclude that implementation would be easier and more successful if the PLI program included a role for school leaders. School leaders help grade-level teams preserve time to meet, and school leaders often determine priorities for local coaches.

This insight led the partners to develop a PLI component for leadership. When the scaling phase began, the partners included it in the PLI program.

Districts and schools are more likely to adopt a program when they can choose which program practices to implement and start small.

During the scaling phase, several districts considered participating but had concerns. The PLI program looked promising but implementing the program as a whole, all at once, in multiple schools would be challenging. They wanted to choose specific components and start small.

When offered that flexibility, the districts signed up. They selected components that mattered to them and wouldn’t interfere with other practices. For example, one district identified a need to build instructional coaching skills and start to establish a consistent approach to coaching. Two districts selected a single school to try the selected program components, with one focusing only on two grade-levels.

The flexibility allowed the district and school leaders to see what aspects of the PLI program fit their needs and consider what they might carry into the year ahead at additional grade levels and schools.

What’s next?

AIR continues to conduct studies of teacher professional learning and help partners and others in the field use evidence to develop, implement, test, and scale professional learning programs. To learn more, see “Spotlight on Teacher Professional Learning”.

AIR

The American Institues for Research (AIR) is dedicated to enhancing the quality of education at all levels by conducting rigorous research, providing thorough evaluation, and delivering training and technical assistance. Discover AIR's education work.

The Danielson Group

The Danielson Group works with school systems across the country and around the world to empower their teachers to be their best by creating professional learning programs and policies that provide the right levels of support all along a teacher's career path. Learn more about their updated Framework for Teaching (FFT).

Learning Forward

Find out more about Learning Forward, an organization that shows you how to plan, implement, and measure high-quality professional learning so you and your team can achieve success with your system, your school, and your students.

Disclaimer

The contents of this digital story were developed under a grant from U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Award No. U411B180032; However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

![Participant Quote: "[The program specialist] was able to explain and tell me reflectively, exactly, what pieces of the process I was using, and what language I was using, she was able to pinpoint, make it clear to me that what I was doing was okay." - PLI Coach](./assets/S6hEWXxVD8/pli-quotes-1-755x755.png)

![Participant Quote: "I think [the PLI Program Specialists] had a nice relationship with the [PLI] coaches, and it was really rewarding both hopefully on their end, but definitely on our end because we saw them really start to move and grow." - PLI Program Specialist](./assets/gxHxAbY2RK/2-755x755.png)

![Participant Quote: "[The biggest success factor was] definitely the team communication and collaboration, just setting aside a common goal for everyone and sharing what's working, what’s not working, and how can we support each other. Then it trickles down into their individual and student goals. So just providing those opportunities as a team to talk about a common goal and how to accomplish it." - PLI Coach](./assets/XdAmAtAJeR/3-755x755.png)